TL;DR

Remember the wild 80s ninja craze? Forget Hollywood, Sweden delivered "The Ninja Mission," a bizarrely charming B-movie with Polish actors, questionable accents, and explosions aplenty. Despite censorship woes and a director with a past, this film unexpectedly conquered the globe, grossing millions. Now remastered in a stunning, uncut Blu-ray, it's a nostalgic dive into a uniquely Swedish take on espionage, featuring car chases, disco, and ninjas armed with more than just shurikens. Dive into this cult classic to see why it became a global phenomenon!

The best Swedish ninja movie with Polish actors ever made

During the 1980s, Bruce Lee maintained his prominence in revival cinemas across Vesterbro in Copenhagen and in private settings, often viewed on illicit, low-quality VHS recordings. However, the emergence of ninja films inaugurated a new subgenre that quickly captivated audiences. For several years, these legendary Japanese ninja warriors were regarded with immense fascination and excitement.

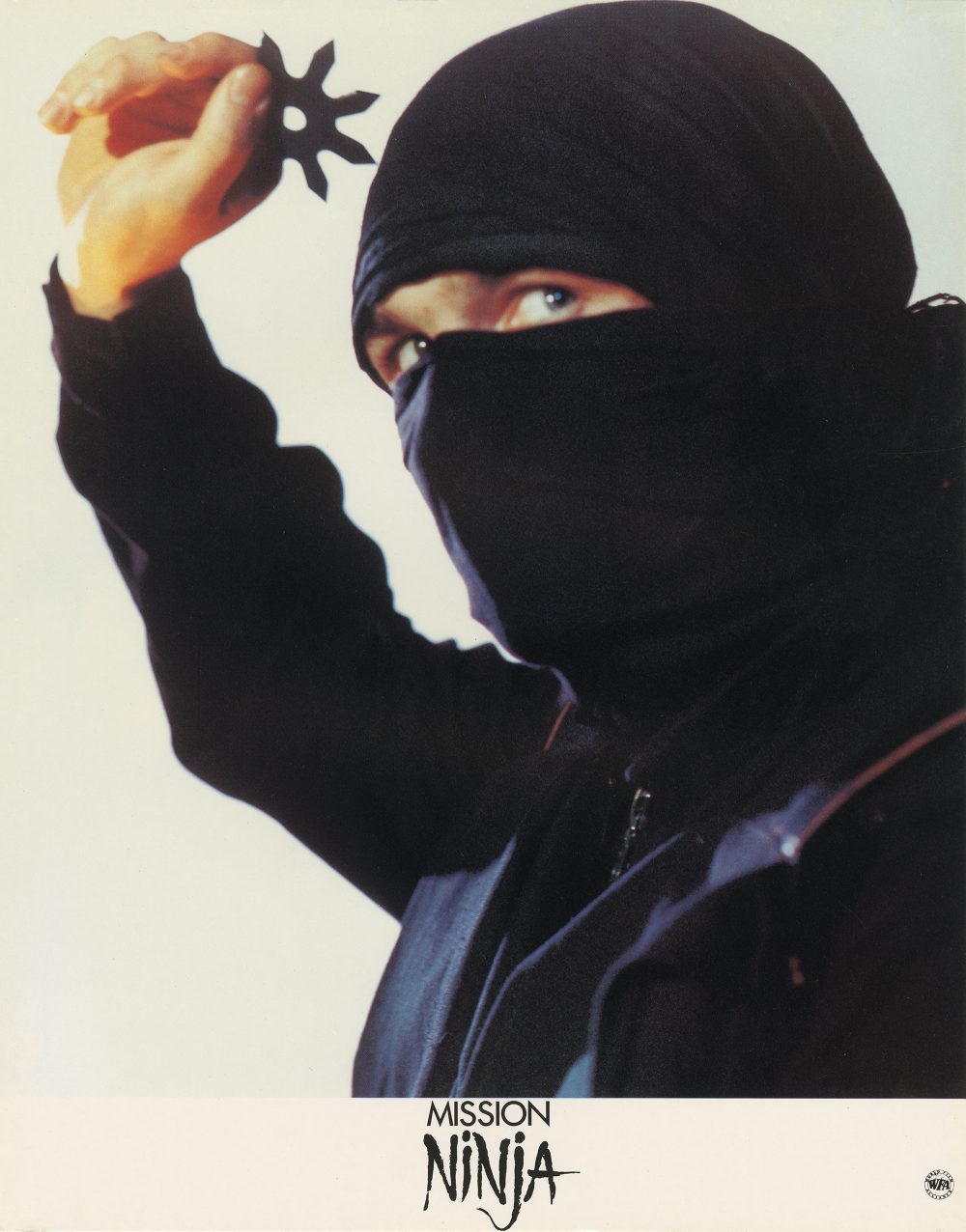

Portrayed as enigmatic assassins and master spies endowed with near-supernatural abilities, moving with silent efficiency in the shadows, ninjas were inherently compelling figures for action cinema. A notable example was Enter the Ninja (1981) starring Franco Nero, though the on-screen combat, particularly the masked figure in the white suit, was performed by karate master Mike Stone rather than Nero himself.

The Octagon with Chuck Norris also stood out. His antagonist, Seikura, was portrayed by Tadashi Yamashita (also known as Bronson Lee). Yamashita was a highly-regarded Japanese karate expert, whose genuine combat skills, much like Norris’s, were clearly evident on screen.

Michael Dudikoff also gained popularity with American Ninja (1985). However, Sho Kosugi (Pray for Death, 1985) was widely regarded as embodying the most authentic portrayal of a ninja.

Swedish censorship evinced a strong aversion to films featuring martial arts combat.

Consequently, films such as Enter the Ninja, The Octagon, and American Ninja initially faced outright bans. Enter the Ninja was eventually released in 1989 on rental video, significantly edited by the distributor, resulting in a reduction of eight minutes.

American Ninja, initially banned in 1985, was later screened in cinemas and made available on rental video. Precise details on the extent of SF’s cuts are unavailable, but it is reasonable to assume that numerous instances of violence, such as throwing stars or sword slashes, were removed.

Sho Kosugi’s films, often more intense in content, predictably failed to pass Statens Biografbyrå (the Swedish National Board of Film Censors). Nevertheless, they became available on rental VHS, albeit subject to substantial cuts by apprehensive distributors, who were operating under duress from fines and potential imprisonment during the fervent anti-video violence campaign of the early 1980s.

However, audiences in Skåne circumvented these restrictions.

Many traveled across the sound by ferry and train to Copenhagen, where films depicting ninjas engaging in combat with sharp swords, smoke bombs, and deadly throwing stars were readily accessible without censorship.

Adjacent to the historic Saga cinema on Vesterbro, Chr. Steinbach’s bookstore offered a range of items, including Hong Kong-imported Bruce Lee magazines, ninja-themed books, and even martial arts weapons such as nunchaku and throwing stars.

Copenhagen in the 1980s offered a notably less restricted cultural environment for genre enthusiasts.

Subsequently, a notable cinematic event transpired.

Sweden produced its own ninja film. The Ninja Mission (1984) was directed by Mats-Helge Olsson, Sweden’s uncrowned king of B-movies. Filming locations included Lidköping Hospital, Rörstrand Porcelain Factory, Fredriksten Fortress in Halden, Norway, and a martial arts studio on Havregatan in Östermalm, Stockholm.

Mats-Helge had recently completed a prison sentence, having borne the sole financial responsibility for Sverige åt svenskarna (1980), a film widely recognized as one of Sweden’s greatest cinematic failures. Undeterred, Mats-Helge was driven by a desire for vindication and refused to abandon his filmmaking ambitions.

He intended to demonstrate to his detractors that his career as a filmmaker was far from over. Promptly, Mats-Helge collaborated with producer Charles Aperia to outline the narrative for The Ninja Mission, for which Matthew Jacobs subsequently wrote the script.

Mats-Helge himself asserted that a then-unknown Jean-Claude van Damme reached out to offer his services as an extra. However, the numerous and often exaggerated anecdotes surrounding Mats-Helge make it difficult to ascertain the veracity of this particular claim.

The Ninja Mission achieved significant international success, generating considerable attention.

In the US alone, it was screened in 90 cinemas. It is reported that the film grossed a million dollars on its opening day. By 1987, it had climbed to second place on the American box office charts.

The successes continued as the Swedish ninjas subsequently gained popularity in Asia. In total, the film was sold to 54 countries. Producer and action film expert Mike Leeder has described The Ninja Mission as “The best Swedish ninja movie with Polish actors ever made.”

Reports suggest the film grossed a total of $250 million. However, it appears improbable that Mats-Helge or the production team from Västergötland received any significant portion of these revenues. The ultimate destination of these funds remains unclear, a lamentable situation for one of Swedish cinema’s most notable international breakthrough films.

Swedish critics received the film negatively.

As anticipated, the film encountered significant resistance from censors. Ten cuts, amounting to over seven minutes of footage, were mandated before the film premiered in cinemas and was later released on video.

For an extended period, an official release of The Ninja Mission on video or DVD was unavailable. This absence stemmed from Mats-Helge’s profound dissatisfaction with the film industry, as he believed he had been both humiliated and unfairly deprived of his rightful share of the film’s revenues—a contention difficult to dispute.

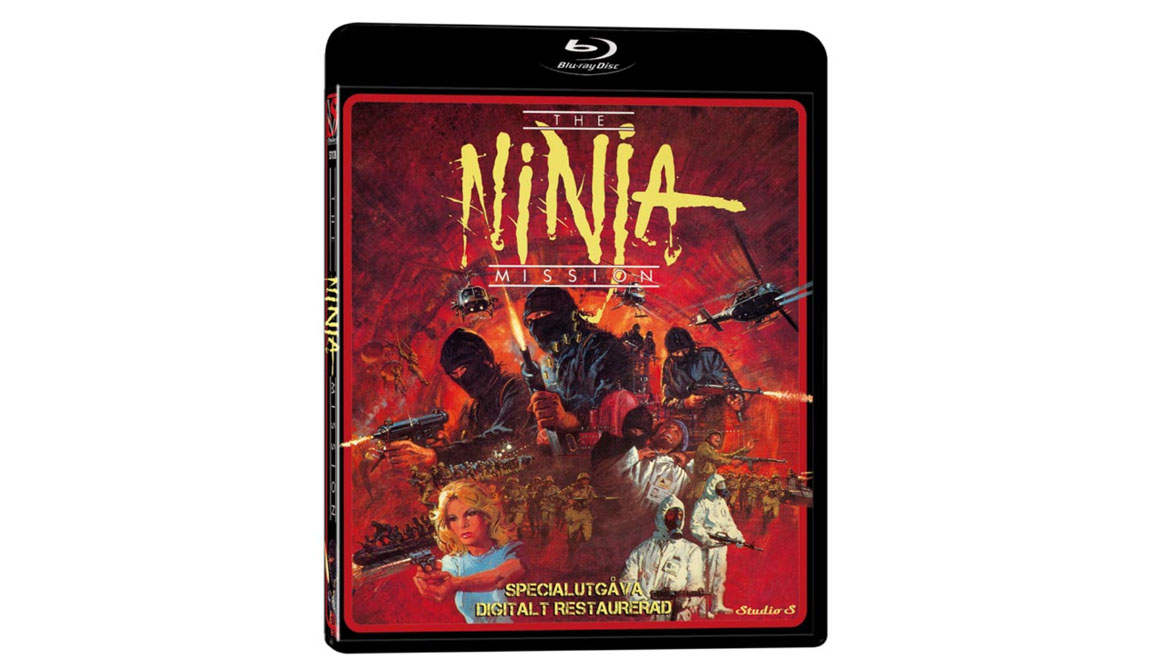

Temporarily, an unofficial, or “underground,” DVD release emerged, distributed by Charles Aperia through his company, Horse Creek Entertainment. However, the cult classic has now received a Blu-ray release: a comprehensive, uncut edition featuring extensive bonus material. This version has been digitally restored from its original 35mm negative, which had remained preserved in an archive for over 40 years.

The narrative is straightforward.

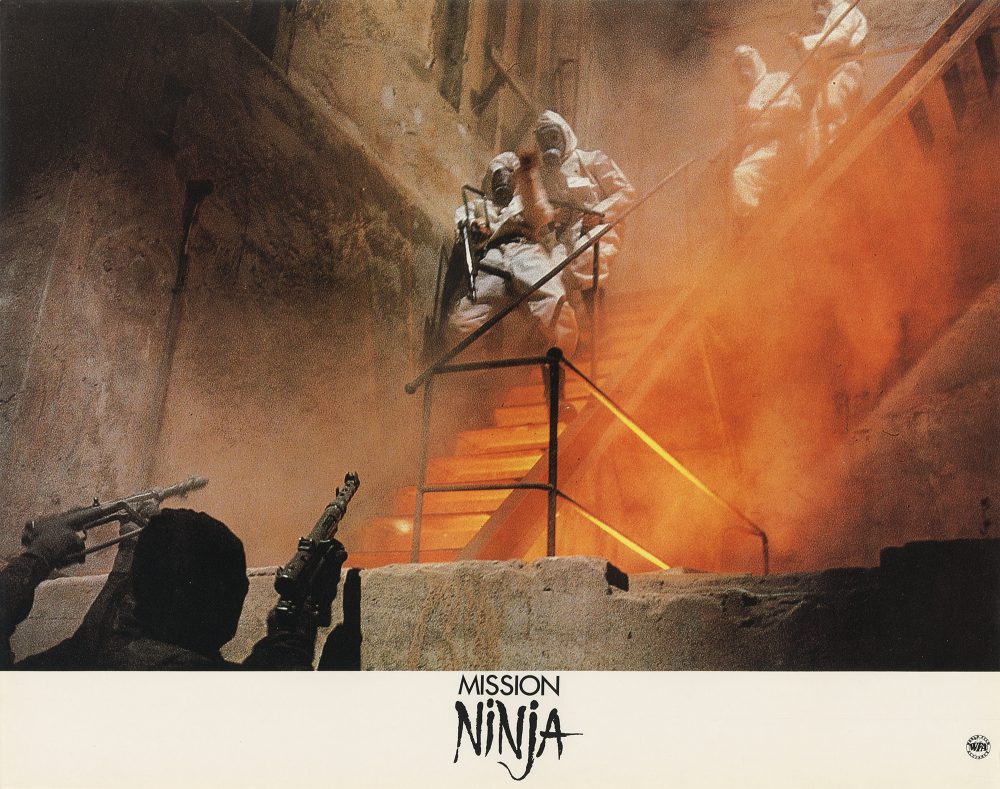

Russian nuclear physicist Markov (Curt Broberg) has developed a new form of nuclear fusion, potentially offering a solution to global energy demands. Concurrently, its misuse could challenge the international balance of power between superpowers. Markov attempts to defect to the West but is apprehended by the KGB.

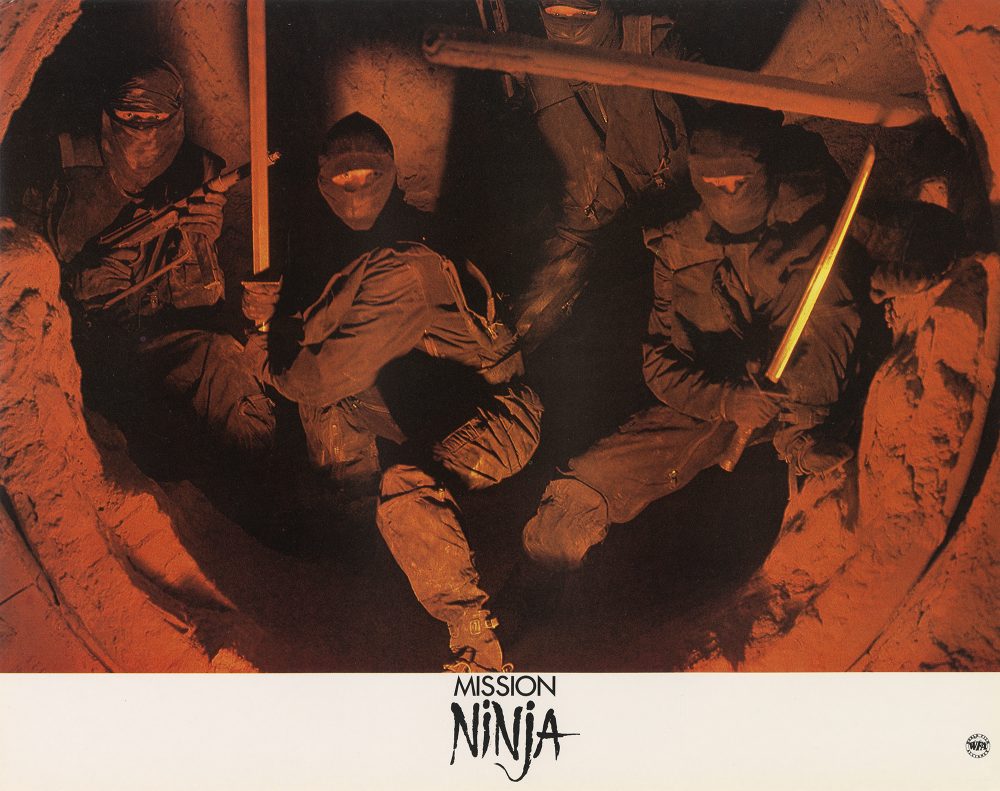

By kidnapping Markov’s daughter, nightclub singer Nadia (played by Polish Hanna Bieniuszewicz, also known as Hanna Pola), the KGB intends to coerce his cooperation. In response, the CIA dispatches a team of ninjas to liberate Nadia and Markov from the heavily guarded Soviet fortress where they are imprisoned. The leader of the ninja squad is Agent Mason, portrayed by the Pole Krzysztof Kolberger, who was credited as Christofer Kohlberg.

When the ninja craze surged, Ninjitsu remained a relatively obscure martial art in the Western world.

This trend of ninja films subsequently led to the proliferation of numerous, often questionable, ninja schools globally. Hardly had the fervor of Sweden’s video violence debate subsided when parent-teacher associations, educator organizations, and other self-appointed moral guardians discovered a new phenomenon to condemn.

Concerns were raised over the emergence of clubs where Swedish youths could reportedly learn techniques associated with ruthless assassins in their leisure time. In the 1980s, Bo F. Munthe (1943–2018) was largely unknown to the general Swedish public. Professionally, he focused on conflict management for various Swedish companies and was a licensed instructor in “verbal judo.” For a period, he also conducted bodyguard training at a company called Personskyddsskolan.

Beyond Swedish national awareness, however, Munthe was a prominent figure, recognized as one of the world’s leading Ninjitsu practitioners. He was sometimes referred to as “the father of European ninjutsu.” Munthe had previously trained in judo, kempo, karate, and jujitsu, among other disciplines. In the mid-1970s, he became the first European to travel to Japan and train directly under ninja master Masaaki Hatsumi, among others.

In 1977, with Hatsumi’s endorsement, Munthe established his own style, “ninpo goshinjutsu mu te jinen ryu,” which roughly translates to “technique for self-protection.” In The Ninja Mission, Munthe portrays the character of Hansen—one of the CIA’s highly trained ninja warriors.

Charles Aperia conceived the idea for the film when Munthe visited his office to submit his novel, Ninja: Mördare i svart (published in 1982 by Lektyr and Saxon & Lindströms förlag). A book from which Munthe had, in turn, drawn inspiration from Andy Adams’ Ninja: The Invisible Assassin (1970), motivating Munthe to commence Ninjitsu training.

Also present in the office that day was Mats-Helge Olsson, seeking funding for a candid camera film. Upon observing the cover of Munthe’s book—depicting Munthe with a sword and a black ninja mask—Aperia promptly declared:

–”We must adapt this into a film!”

Thus, the production began to take shape.

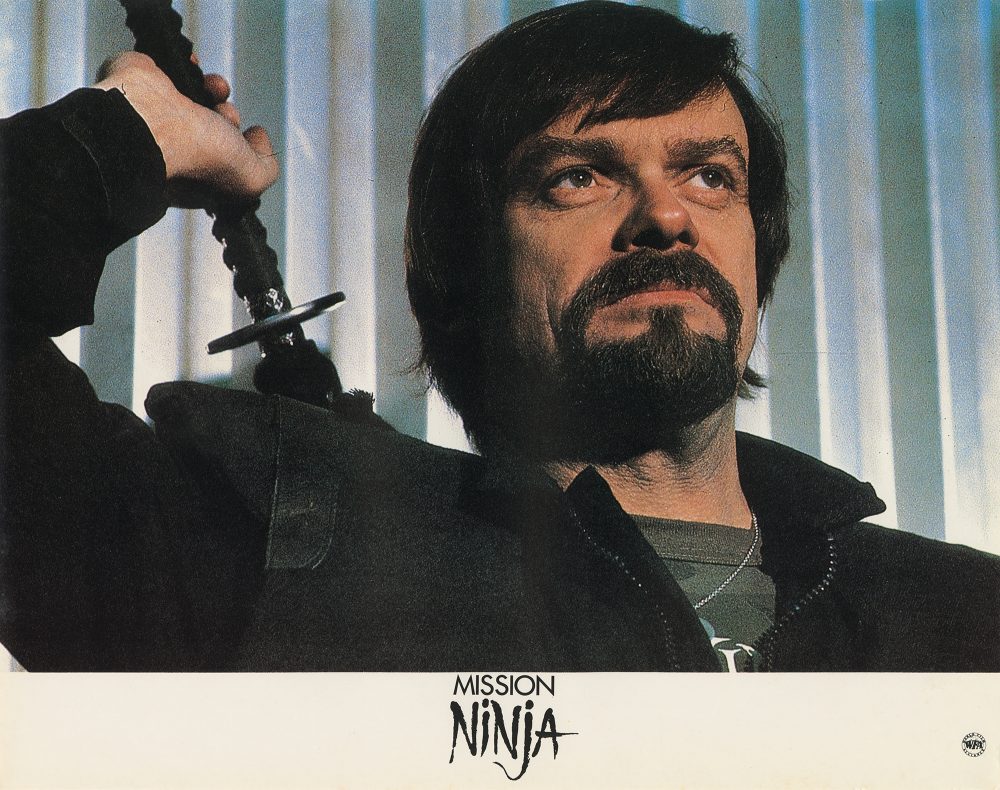

(Viewers may note a cameo by Mats-Helge, portraying a bearded Russian agent involved in abductions within the film.) Munthe subsequently collaborated with Mats-Helge on another film, taking a minor role in Animal Protector (1988), which starred a frequently inebriated David Carradine.

Following the success of The Ninja Mission, there was a noticeable surge in interest among Swedes to learn Ninjitsu.

Luxman advertised its stereo equipment on large billboards in Stockholm’s subway. The ninjas depicted on these prominent posters were from Bo F Munthe’s school. Munthe reportedly received no monetary compensation, stating that his sole remuneration was a complimentary stereo system. However, the billboards prominently displayed the phone number for Munthe’s club, leading to a significant influx of young individuals to the new dojo on Jungfrugatan in Stockholm.

My personal visit to the dojo, however, proved to be a disappointment. The training focused primarily on unarmed techniques, or “taijutsu,” with no visible evidence of the throwing stars, smoke bombs, swords, or ceiling-climbing black-clad figures commonly depicted in cinema.

Munthe himself appeared as a fatigued and overweight older man, slumped on a stool in a corner of a rather dreary basement locale, displaying a bored expression. Meanwhile, his assistant Sven-Eric Bogsäter (who also plays a ninja in the film) loudly instructed a handful of individuals running and rolling on the sweaty wrestling mats.

This experience demystified the idealized image. I recall returning home, and the following day, resuming visits to Copenhagen’s cinemas, where the cinematic portrayal of ninjas consistently met expectations.

Subsequently, it was learned that Munthe suffered from asthma and had been compelled to reduce his activities following two heart attacks. Training at the schools in Sweden and England was sustained by his assistant trainers. Munthe also acknowledged being an ineffective businessman and suggested that success had negatively influenced his judgment.

The precise implications of these statements, beyond financial losses for some of his business partners, remained undisclosed by Munthe. Subsequent “political battles” prompted him to resign as head trainer for Masaaki Hatsumi, leading him to develop and teach his own ninja style.

The new edition of The Ninja Mission offers a welcome opportunity for nostalgic re-evaluation.

The film is notably dark, at times obscuring on-screen action. This aesthetic, however, is a common budgetary technique to compensate for limited resources and unavailable locations, characteristic of Mats-Helge’s directorial style. Numerous scenes feature characters entering and exiting rooms with urgent exclamations like “Let’s go!” and “Hurry up!”

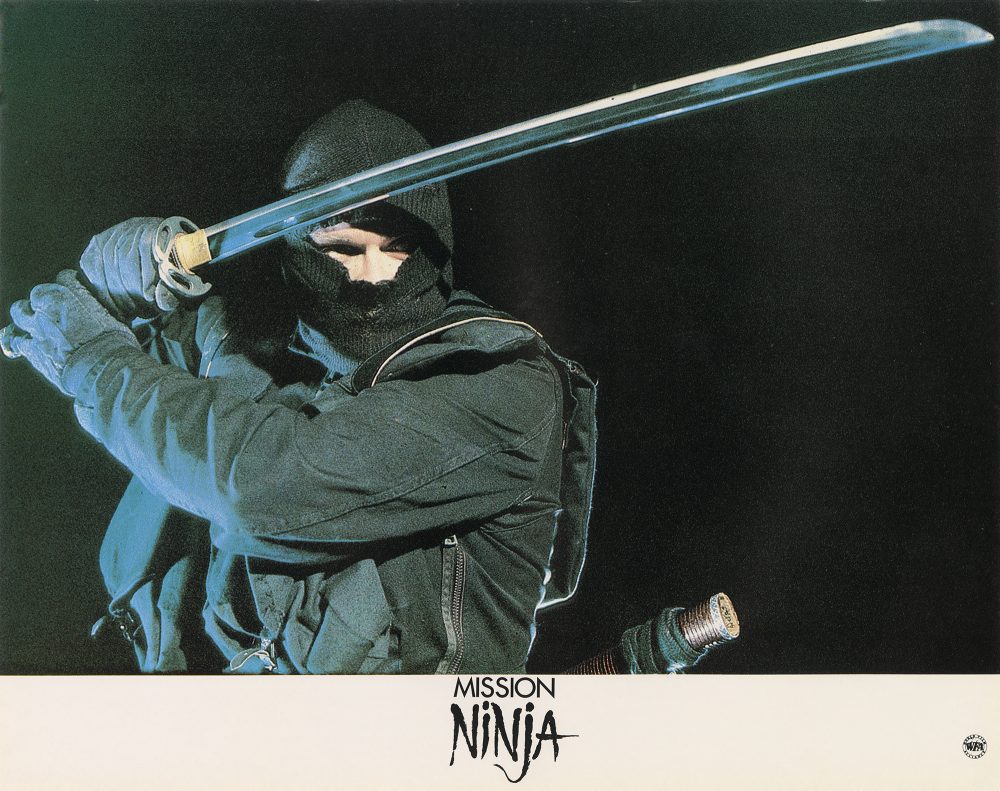

Discerning viewers may observe that the film’s Russian soldiers are equipped with standard Swedish military weapons (m/45). Furthermore, it is somewhat incongruous that the film’s ninjas predominantly utilize bombs and automatic weapons rather than engaging in extensive martial arts combat, with only a few actual fight sequences present.

The black-clad warriors also employ several unconventional weapons, including a device that fires poison darts capable of causing antagonists’ brains and hearts to explode—a contrivance reminiscent of Q’s gadgetry in a James Bond film. The film occasionally features graphic violence, including slow-motion sequences, which were particularly anathema to 1980s censors.

Casualties are frequent, particularly among the Russian antagonists, while the ninja warriors appear largely impervious to gunfire. A notable narrative inconsistency arises from the ninjas’ choice of black attire when operating in snow-covered environments.

Most actors deliver their lines in English with a distinct Swedish accent, and one scene, ostensibly set in the Soviet Union, clearly displays a road sign with the Swedish text “Mötesplats” (Meeting point). However, such production anomalies contribute to the inherent charm of low-budget action films produced expediently in locations like Västergötland.

The Ninja Mission retains its status as one of the 1980s’ most engaging cult classics within the genre. The availability of a commendable new release, presented in updated condition and featuring Swedish ninjas alongside car chases, instances of nudity, and disco singing, represents a significant cultural preservation effort.

The Ninja Mission serves as a compelling piece of 1980s nostalgia. While admittedly a quintessential B-movie, complete with its characteristic imperfections and production shortcomings, this newly restored version is technically impeccable. Its release on Blu-ray, revitalizing a cherished 1980s favorite, is a notable cultural contribution.

For enthusiasts of the genre, this release offers a comprehensive cinematic experience.

Studio S sent review copies for this test. Senders of material have no editorial influence on our tests; we always write independently with our readers and consumers in focus.