TL;DR

Vlad the Impaler's cruel legacy inspired Bram Stoker's Dracula, but the game *Vampyr* offers a fresh take on the vampire mythos. You play as a doctor turned vampire, hunting for answers in a vampiric London after accidentally killing your sister. While the premise is strong and the narrative engaging, the game struggles with its identity, leaning heavily on repetitive combat instead of embracing horror or stealth. Despite solid visuals and decent performance (especially docked on Switch, where portable text is tiny), technical issues like crashes and slow loading times persist. *Vampyr* boasts interesting concepts and a compelling moral dilemma about humanity vs. power, but its unfocused gameplay prevents it from reaching its full potential. Want to know if this dark adventure is for you? Dive into the full review to find out!

Vlad III Dracul, also known as Vlad Tepes (“The Impaler”), was born in Transylvania, Romania, circa 1431. The name Dracul originates from “Drachen,” a German order award bestowed upon his father for wartime bravery, signifying “dragon.” However, in Romanian, “drac” translates to “devil.” This moniker, combined with Vlad’s iron-fisted rule, dispensing of justice, and notorious cruelty towards enemies, ultimately contributed to the legend of Dracula, the iconic vampire popularized by Bram Stoker. Given the saturation of vampire-themed media across films, books, television, comics, and games, Vampyr initially seemed like another addition to an already crowded genre. However, the intriguing premise of playing as a vampire piqued my interest.

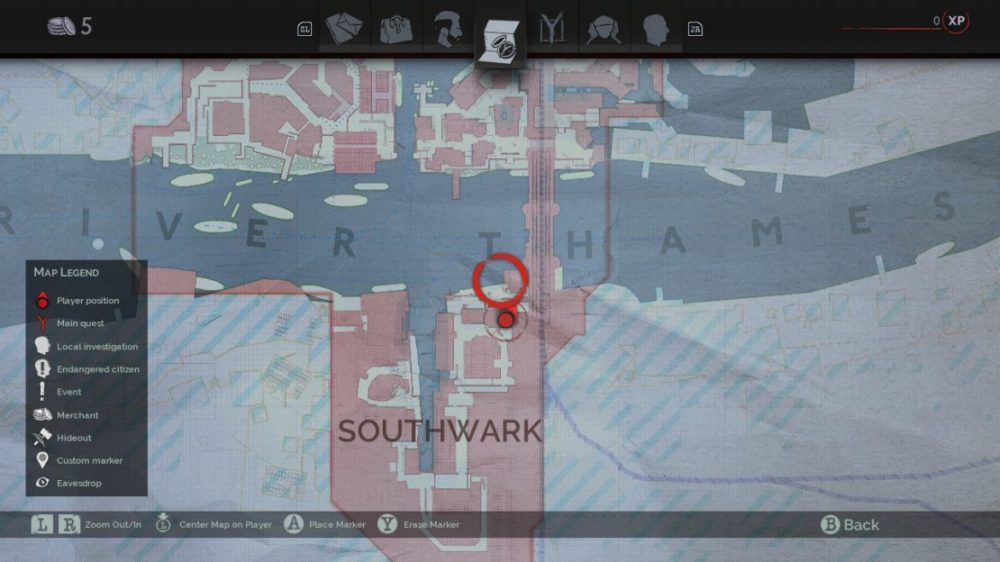

The game begins with the protagonist awakening amidst a field of corpses, disoriented and suffering from an intense thirst. Driven by instinct, he attacks the first human he encounters, only to discover, to his horror, that he has murdered and consumed the blood of his own sister. He is subsequently hunted throughout London as he seeks answers and a resolution to his vampiric condition.

Vampyr establishes a compelling premise. The protagonist’s transformation into a vampire and subsequent slaying of his sister, coupled with being hunted by authorities and other citizens, sets a dark tone. However, the game encounters issues as it progresses. Players can choose to feed on the characters they encounter, gaining advantages at the cost of their humanity and morality. While this moral dilemma is interesting, the core gameplay loop revolves around combat against waves of enemies, a design choice that feels somewhat incongruous. The reliance on generic, repetitive battles with nameless adversaries seems like a missed opportunity to explore the nuances of being a vampire.

Vampyr might have benefited from a greater emphasis on horror and stealth elements, rather than transitioning into a more action-oriented experience. Nevertheless, the game exhibits solid production values, and the narrative remains engaging. Some of the dialogue can occasionally feel overly verbose. The visuals are appealing, and the game generally runs smoothly, even on the Nintendo Switch’s hardware. Docked mode is preferable, as portable mode suffers from the same issue as Call of Cthulhu; the text becomes difficult to read. This highlights a recurring issue with ports to the Nintendo Switch: text legibility in handheld mode.

During my playthrough, I encountered a rare issue: the game crashed, locking up the entire console. A full restart was required to resolve the problem. This may be attributable to the game’s demanding technical requirements, similar to Call of Cthulhu, which was also recently released on the Switch. Other issues include slow loading times (although Vampyr’s loading is notably faster than Call of Cthulhu’s) and occasional crashes. First-party Nintendo titles rarely exhibit these problems, so there is an expectation that developer Dontnod will address these issues with future patches.

In conclusion, Vampyr receives a passing grade, owing to its interesting concepts and innovative elements. However, the presence of bugs and the excessive focus on a somewhat misplaced combat mechanic detract from the overall experience. The character upgrade system, reminiscent of a role-playing game, feels somewhat disjointed, as if the developers were unsure of the game’s core identity and attempted to appeal to too many genres and player types. A more sophisticated “Vampire simulator,” exploring the implications of eternal life, would have been preferred. Perhaps in the future. In the meantime, Vampyr is worth considering.